Touching the Art with Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore

A conversation about the iconic queer author’s book tour last winter and resisting structural violence from Baltimore to Gaza.

Touching the Art is the title of Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s most recent book. The Seattle-based queer writer and activist began 2024 on an East Coast book tour reading from this hybrid research-based memoir centered around Mattilda’s relationship with her late grandmother, abstract painter Gladys Goldstein. “When I started working on the book, I started by literally touching her art,” she explained to me. “I was taking these handmade paper works out, one by one, and touching them to feel what comes through.”

What Mattilda discovered in the process goes well beyond her grandmother’s art. The book moves from the intimate and the familial to the structural and historical, delving into the violent legacies of white flight, displacement, and Jewish assimilation in Baltimore, the city where Goldstein lived until her death in 2010. And on the personal level, Mattilda shares how her grandmother provided an early model for a creative life along with the support and nourishment for her own youthful creativity, introspection, empathy, femininity, and softness—for “everything that made me queer.” But then by her early 20’s, when Mattilda’s work and life was becoming unapologetically queer, suddenly Goldstein saw everything as “vulgar.” Touching the Art “circles around that abandonment” while weaving these pieces, from the intimate to the systemic, together to exist on their own and in conversation with one another.

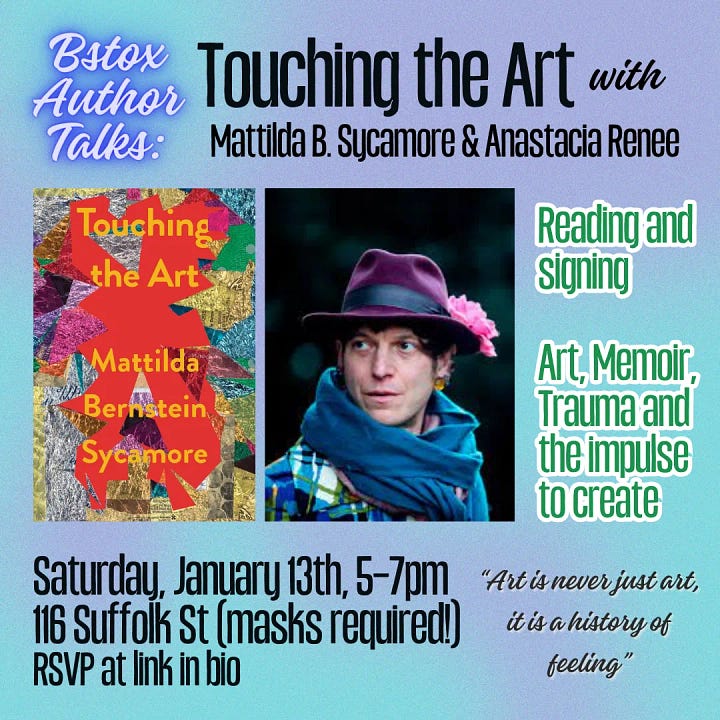

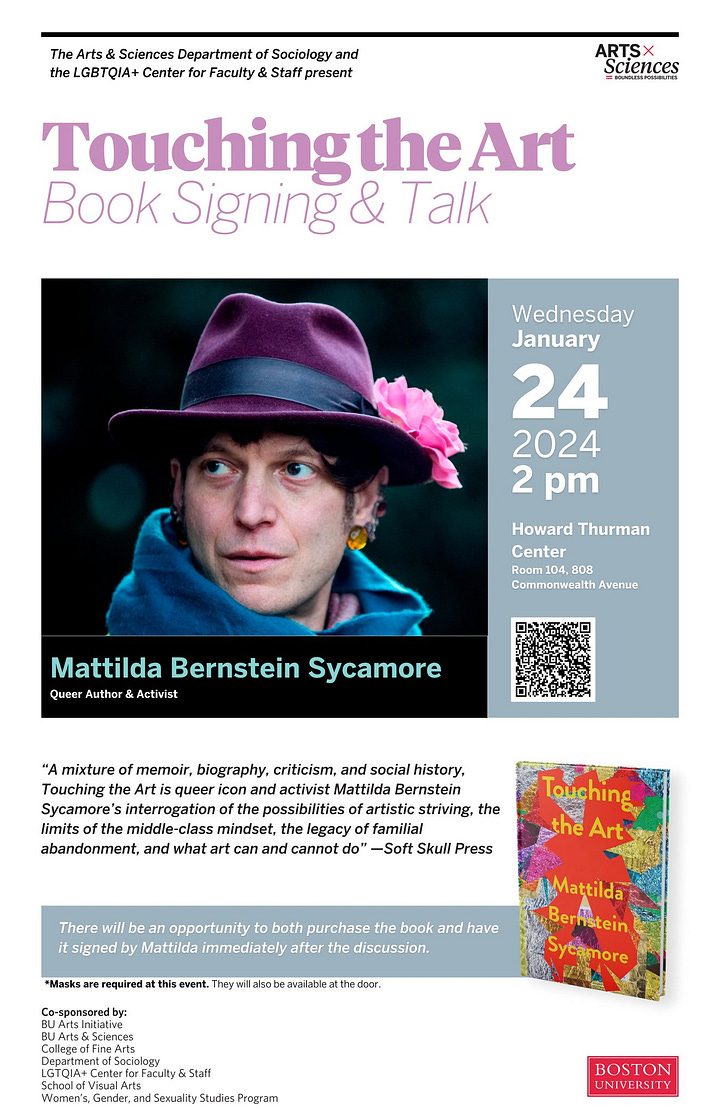

This past January, I had the immense pleasure of connecting with Mattilda on two different stops on her book tour. First in New York City, at her reading and conversation with writer and artist Anastacia Renee at Bluestockings Cooperative Bookstore, and then at Boston University where I introduced her talk. In between these events, we had the following discussion about the responses to Touching the Art, Mattilda’s time researching and living in Baltimore, and her experiences earlier on tour in the wake of the growing movement against Israel’s assault on the people of Gaza.

Matt Dineen: I think one of the first times you and I met, when I was living in Philadelphia, you were taking a train down to do the first event at Red Emma’s, the amazing infoshop and social center in Baltimore. They had just expanded into this massive new space. And I’m thinking about Red Emma’s, and some of my conversations with collective members there, about the incredible community organizing that has happened in Baltimore and how they’ve been able to create a space to expand and to be a resource for organizers in the community. And I was just thinking about the organizing there after the murder of Freddie Gray by the Baltimore police. I’m wondering if that was before you were living there? Were you starting to write this book, after the uprisings?

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore: So I was in Baltimore in 2018, and Freddie Gray was murdered in 2015. But that legacy was still very palpable in several ways. One of the ways was the hyper-policing, privatized policing. So where I was living in Charles Village is right near Johns Hopkins, which is sort of the dominant institution in Baltimore, in terms of resources. And when you go out on the streets, especially at night, there are more private Hopkins security in the neighborhood—not on the Hopkins campus, but in the neighborhood—than there are pedestrians.

So being in Baltimore, and tracing the house where my grandmother grew up, I went to the neighborhood that she refused to name. When I asked her if she ever went back to the neighborhood where she grew up, she just said you can’t. And I knew that meant it had become a Black neighborhood, and that her racism, and the segregated mentality of Baltimore, meant that she never went back.

One of the people I was able to interview was her childhood best friend and she was 101 at the time, but she was remarkably cogent. She told me things that, otherwise, I would not have known. And one of them was where Gladys grew up. So I was able to go to that neighborhood and to see the way it has been destroyed by decades of disinvestment and hyper-policing and predatory lending. But it was the moment when I realized that she grew up 5 blocks from where Freddie Gray was murdered that that palpable legacy became so clear.

Many white people would like to think that fleeing to the suburbs was about a better life for their family, right? This notion of upward mobility, and that this is going to create a better life. But that legacy is the legacy that doomed these neighborhoods, and it started at a structural level. It started with redlining and with racist governmental actions, right? But the fact that people participate makes it possible.

And so, when I'm looking at the history of Jewish assimilation in Baltimore, Jews were prevented from owning property in most of Baltimore. So Jews were both victims of structural racism and beneficiaries and active participants because they were sometimes the only people who would extend loans to Black people at a time when Black people couldn't get loans, but they also benefited from blockbusting and redlining. And then renting to Black people in the neighborhoods they had abandoned, but still owned properties, at inflated rates. And this is an ongoing legacy.

Part of touching the art for me is saying that art can never be pure. It's formed by us and by the legacy that forms us.

For me, it comes back, in some ways, to this question about art. I think we're taught that art is something pure, that it exists in a vacuum. And, I think, abstraction as well. Gladys was a loyal abstractionist, she spent decades perfecting these intuitive techniques, she was meticulous about letting the imperfection remain and become part of the composition. She scoffed at traditional figurative painting, she thought it was derivative. She had this highly refined way of thinking about art and space and materials. But at the same time her racism, and the segregated mentality of Baltimore, the city that formed her, meant that she couldn't even consider going back to the neighborhood where she grew up, because it had become a Black neighborhood. And this is liberal Jewish assimilation that I’m talking about. But she really believed in children, and children's art. And the school that she went to, a high school that at the time, in the 1930s, was a school for girls, so it was gender-segregated, and white only. And now, on the same grounds, this is a school that is not legally segregated, but it's almost entirely Black students. And I wonder, what would she have learned from these kids if she had gone back?

Part of touching the art for me is saying that art can never be pure. It's formed by us and by the legacy that forms us. And so it exists in that context. So looking at history and looking at structural violence and looking at the creative potential, all have to exist side by side. And abstraction, for me, is a way of transcending everyday drudgery in order to imagine something else. It can illuminate our experience in the moment too. But I think so often—and this is certainly true of Gladys and her entire generation—and this is still true of so many in the art world, this notion that art supposedly exists outside of these larger forces. And so part of the book for me is about rejecting this notion of purity, making all the necessary connections, even or especially when they are difficult.

Well, you spend all the time researching the book, writing it and now that the book is out in the world and people can physically touch your book. They're touching the art. I'm so curious to hear about the responses to the book and these discussions you've been having on your book tour.

There have been a lot of amazing responses, and some that really surprised me. So, for example, I was interviewed on the NPR affiliate in Baltimore on a program called On the Record with Sheilah Kast, which does a very good job of framing the book for a Baltimore audience. And someone wrote to me after hearing that interview, and he said that he grew up 3 doors down from my father. They went to school together. He knew my grandmother, my grandfather, my great grandparents. And that was fascinating. This is not the neighborhood where Gladys grew up, but it's the neighborhood where she moved after she got married in 1941, at the time it was a white middle class neighborhood. And so I went to that neighborhood, which is where she raised my father. So the neighborhood where she grew up, you can see how it has been destroyed by structural violence. And by destroyed, I mean, like half the buildings are boarded up or have burned down.

And so the neighborhood where she raised my father, which is where this person grew up, is this beautiful, very preserved middle class neighborhood. Now the only difference, besides that all the houses are older and the trees are bigger, is that it's basically an all-Black neighborhood. And this person said to me, after hearing the show, he said, “I'm the white person who's stayed.” So I said to him, “Oh, does that mean your parents stayed, and you live in their house?” He would be 80 now, so the same age as my father, if my father were alive. And now that his parents have died, he still lives in the house, and he said that his parents, after they stayed, as the neighborhood was transitioning in the 1960s, that their relationships with their Black neighbors, once it became an entirely Black neighborhood, were so much deeper than any relationships they had ever had with their white neighbors.

And that's just one person, but that to me, is so instructive in a certain way. Like, what if no one left? His parents stayed because they were integrationists. So it was a political choice. And so that was one very interesting conversation. Also what's been interesting is relatives of mine reading the book who are incredibly moved, and deeply inspired by all the layers, seeing how they also reflect the layers of their lives.

I know there was an event you did on this tour in New York, at the Jewish Museum, where there were people that didn't like some things you were saying about the state of Israel? I would love to hear more about that.

Right. When the book was coming out, there were three particular audiences I was thinking that I really wanted to be exposed to the book that might not be my typical audience. And that's: Baltimore, the art world, and Jewish institutional life. And the Jewish Museum is at the center of two of those worlds, the art world and Jewish institutional life, and so I started my event by saying I was very excited to do this event there. And I noted that the 92nd Street Y, another high-profile Jewish institution that's right around the corner, had canceled an event with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen, after he signed an open letter criticizing the Israeli government’s assault on Gaza. And then, when other authors pulled their events in protest, the 92nd Street Y cancelled all of their literary programming for the year. So at the Jewish Museum, I said that I'm sure there are many people in this audience, including myself, who have signed open letters criticizing the apartheid state of Israel and its genocidal campaign of ethnic cleansing in Gaza that continues as we speak, with the full support of the US government. And that if touching the art means anything, then it has to mean touching everything that comes through. And that the least that any institution can do right now is to amplify the voices of people who are being silenced: Palestinians and anti-Zionist Jews and anyone else who's being silenced in this moment of complicity. And so I'm grateful to be here tonight at the Jewish museum, in a Jewish institution that has not cancelled this event. (laughs)

The immediate response was elation, most of the people in the room were applauding, right away, but simultaneously, there were 6 or 7 people who got up to leave. This is at the very beginning of the event. One person actually said, “Where did you go to school?” Which I thought was hilarious because that is an essential theme in the book because when I decided to leave college at age 19 it was this big moment of friction with Gladys. I looked to her as a model for an artist's life, and so I saw her as rejecting these institutions, right? But I was wrong. She believed in making art within middle class respectability. And middle class respectability was everything that would kill me. It camouflaged the violence, not just of racism, classism and misogyny, but also my father's violence. He sexually abused me, and hide this with his success. And so, when this woman said, “Where'd you go to school?” I said, “Well, that's a topic in the book!” (laughs)

And then this other woman was yelling at me, “It's not genocide!” She just kept yelling, over and over again. So then these people left with their husbands, 6 or 7 of them. And then the event continued. I read from the book. I had a conversation with Chloë Bass, who is a conceptual artist, it was deep and intimate and wide-ranging. And then I read from a part in the book where I speak very directly to my own familial experience of being really proud of my Jewish heritage as a kid. And going to Hebrew school, even though my parents were non-observant, but they gave me the option. And I was really enamored of the Hebrew language, not knowing its history. Also of some of the rituals in my Hebrew school, one of those was to plant trees in the Negev desert, allegedly to stop desertification. Now, I didn't know at the time that this was actually part of an Israeli government program to destroy Palestinian villages, to make way for Israeli settlements. They planted the trees to cover up these villages after they wiped them off the map.

And so I'm talking about some of these myths of Jewish institutional life. And in that moment, I think it was the same woman who asked me where I went to school, she had stayed. She would boo every time I said Gaza, but she stayed, and seemed calmer until that moment. She started yelling something like, “This isn't Jewish,” or “You're not Jewish.” Which, of course, is the height of irony, because this is the one moment, when I'm literally saying “I went to Hebrew school.” (laughs) And so this is that irrational panic, right? It's like, “Oh, my god, you're challenging the myth that I believe in?”

So a book is a living object. A book never ends, I think. It exists in the world as the world is now.

Because in the event I talked about how Gladys had decided that everything I did was vulgar. That was the word she kept using once my work became unapologetically queer. And then I was talking about her contemporary, Grace Hartigan, who said that she embraced everything that was vulgar and vital about American life. That was her artist’s statement. Frank O'Hara, the famous gay poet of the New York School, was her best friend, and, when they had a falling out, he wrote that he hadn't noticed before this vulgarity of spirit in her work, obviously forgetting that she said she embraced everything that was vulgar. So I said, I think this question of vulgarity is a generational question. And so, at the end of the event, Dan Fishback, who is a queer playwright, asked a question where he said, “Do you think that anti-Zionism is vulgar?”

And so it made me think about that childhood experience where you're planting trees, this wholesome act. What could be more nourishing, right? But actually, what you're doing is covering up genocide. And I think there are some Jews who are ideologically Zionist, who have a lot of institutional power. But I think there's a much larger group of people who want to believe that mythology and will to hold on to it, no matter what, even if they do not agree with the Israeli government they will never say anything to stop the genocide, there’s this fear of letting go of this myth of Israel’s innocence, and also a fear of social ostracism if they actually speak the truth. People might stand up and scream at you at your event, right?

So a book is a living object. A book never ends, I think. It exists in the world as the world is now. And so that was a conversation that I may not have expected when I wrote the book, but also it was a moment of connection, right? Even the people screaming at me. (laughs) We were there together, experiencing something, and they were reacting. And so I was glad that I had that opportunity, because I think that most Jewish institutions are complicit in this kind of Zionist ideology. Of course, we have groups like Jewish Voice for Peace and If Not Now, and there is a really exciting outpouring of radical, anti-Zionist direct action. But the dominant institutions, they are Zionist by default. And so I think it makes it all the more important, in a moment when I did have that access in an institution like the Jewish Museum that had certainly not made any statement condemning the genocidal policies of the Israeli government that are continuing in our name. So, in some ways, that was a very full experience of both the book and these larger historical contexts, and how they play out right now in our lives.

I want to end with a quote from the book Touching the Art that I think is also connected to this historical moment. You write, “Against structural violence, feeling may be our only hope.” Can you say more about that idea, especially in this current moment we're in right now?

I start the book by literally touching the art because I really wanted to start on the terms of the art. And on the terms of abstraction, but without the limits that abstraction can sometimes impose. To feel everything that comes through. Not just about the art, but everything. And so some of that is, of course, what we're never supposed to talk about. Like my father sexually abusing me. Or my grandmother abandoning me. The book, in some ways, is about what I still have, that she gave me as a child, which was this idea that everything was art. That you walk around in the world and your everyday experiences, the way you look at things, is what forms you. So if you see a leaf, and you pick the leaf up off the ground, and you look at it in the light, and it totally changes. You pick up a crinkled piece of foil on the ground, and you look at the light that reflects, and you see how that is a work of art on its own. So this idea, that creativity was everything, was a myth. But it still saved me.

And the violence is always there. And I think that when we silence ourselves is when we become complicit. But also I think that resistance is not only what we think it is.

So I think for me, Touching the Art, like I said at the Jewish Museum, it means feeling everything that comes through. When I first started writing, I was like, “Oh, no! What's my father doing here? I've already written about that trauma. I don't want that in here.” But of course it has to be here. You know, he is the link between me and her. And the violence is always there. And I think that when we silence ourselves is when we become complicit. But also I think that resistance is not only what we think it is. It needs to be direct acts of challenging the status quo and pushing against structural, interpersonal, intimate, familial violence at every turn. It has to be all of that. But I think it's also about feeling. Because when we lose our ability to feel, we lose our ability to resist.